During Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990), Beirut was witness to a series of illegal and unethical demolitions that instigated the erasure of the city, memory, and identity, launching Beirut into a new era of collective amnesia.

In 1975, the war was situated in the centre of the capital where a demarcation line also known as the green line divided the country into east and west Beirut. The area was abandoned by residents due to the ongoing dangers posed by Muslim and Christian fighters on either side of the line. The war spanned two years, before arriving to a cease-fire in 1977. Signs of life, particularly in the bustling souks (markets), slowly started creeping back in before the war expanded to other parts of the city. At that time, the city was abandoned and deserted once again, and access to the city was once again prohibited.

The fighting caused destruction to the city; however, a series of secretive illegal demolitions were conducted. Literary scholar Saree Makdisi counted four series of demolitions that took over the city.1 On the pretext of cleaning up the centre after the Israeli invasion, a first series of demolitions in 1983 erased parts of the souks mainly: Souk Al-Nouriyeh and Souk Sursuq, along with some sections of the Saifi area. The second series in 1986 was similarly executed without the necessary demolition requests from governmental institutions. As Nabil Beyhum wrote, the demolitions were executed by the company OGER led by the late Prime Minister Rafiq El Hariri in preparation for an envisioned masterplan.2 At that point, therefore, the destruction caused was not due to the war but rather the deliberate intention of demolition of buildings. While the first two series of demolitions were executed illegally without any public or governmental oversight, the following demolitions were carried out under a form of legality. By 1991, the government’s abdicated its role as the prime decision-maker of the redevelopment of Beirut. Hariri’s firm OGER would later come to be known as Solidere that became the principal agency of the reconstruction plans. As a result, Makdisi claimed:

Thus, without regard to the public – or even to those whose property would be expropriated by the company – did Solidere come into being the ultimate expression of the dissolution of any real distinction between public and private interests or, more accurately, the decisive colonization of the former by the latter.3

The demolitions of 1992 and 1994 although legal, were executed haphazardly with the help of explosives that excessively damaged the buildings and their neighbouring structures.4 The centre became unrecognizable as Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury wrote: “We enter the Square but do not find the Square.5 The new vision of the city presented by Solidere eradicated the centre and left few monuments and areas intact.

Consequently, the reconstruction project was implemented first erasing the memory of the war that had just occurred and second obliterating the buildings and their significance in shaping the Lebanese identity and collective memory. Journalist Khaled Saghieh concluded “[…] the reconstruction project becomes a war not on buildings, but on the city’s memory. War for the sake of forgetting”.6

Through the series of demolitions, a large number of political holes began to appear in the urban fabric. With this reconstruction plan in effect, excavations intended for laying out foundations led to the revealing of deeper gaping holes while exposing past archaeological traces. Taking into consideration that the destruction of buildings started in 1983, the holes would have remained present and unfilled for a minimum of 6 years, before the official launch of the reconstruction project.

Building the archive

The building of the archive began with the collection of locations of political holes.

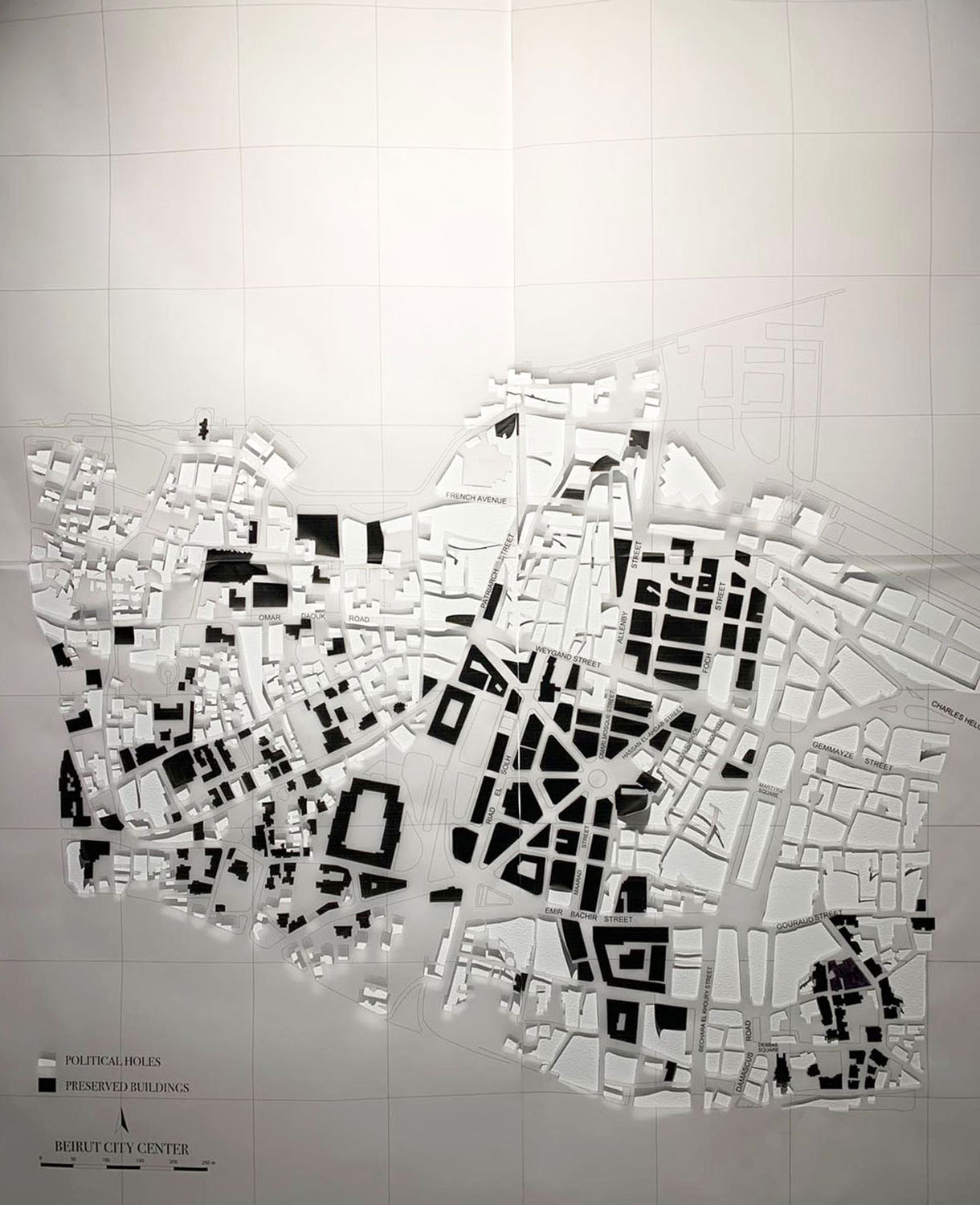

The location of the political holes was informed by the work of researcher Heiko Schmid. 7 Guided by a legend, the map depicted the different periods of demolitions and the conserved buildings. This reading of the city explicitly revealed the locations of the political holes, as well as the number and scale of demolition of buildings over the years. The map showed the “demolitions till 1983” and “demolitions till 1991” as part of those that occurred during the civil war. This map also revealed an additional demolition period “till 1998” where a large number of buildings of the city were demolished. This map was then implemented on subtractive representations (fig. 1) on a map and digital mapping. Based on Schmid’s map, the digital map revealed the extent of the demolitions and some discrepancies.

Figure 1: Subtraction of political holes on Beirut map. By author, 2019.

Comparing the past city to its present state, reveals the major differences in its density where the demolished buildings were consolidated into one lot creating ‘islands’ in the city. Further comparisons between this map, and Google Earth’s historical imagery revealed the past and present political holes in the city. Due to the large-scale demolitions the political holes were denoted as areas according to the Google Earth historical aerial view of 2000 (fig. 2).

Figure 2: Digital Mapping of demolition based on Heicko Schmid's map. By author, 2020.

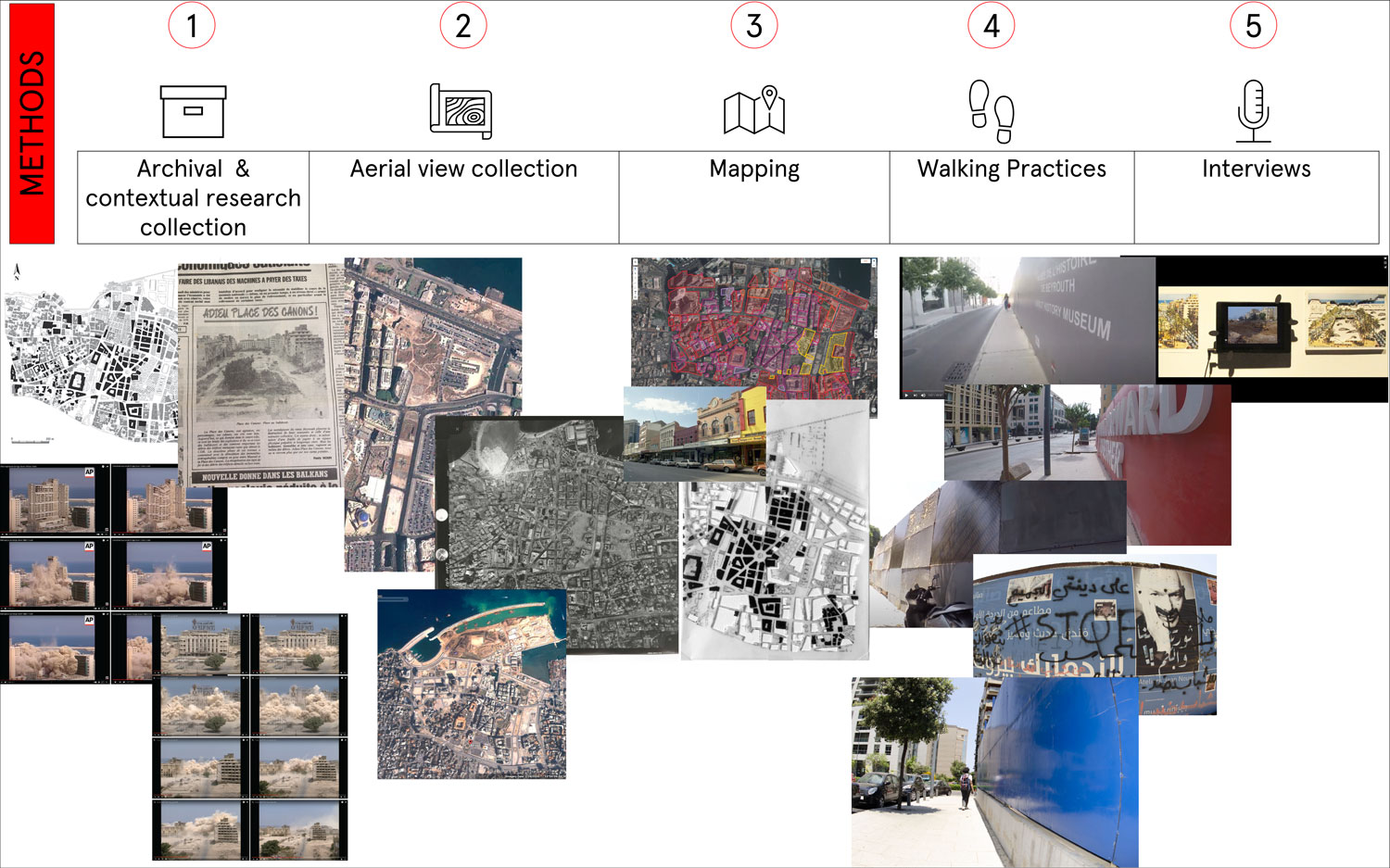

Drawing from Schmid’s map, each ‘Area’ was annotated with the different phases of demolitions that took place on it. Sometimes, the same area is divided into zones that represent different functional hole occurrences such as: a razed hole, an excavated hole, a parking hole, a hole with a conserved building with varying timelines. Using archival research, collection of aerial views, mapping, walking practices, and interviewing each political hole area was documented and recorded as part of the archive (fig.3).

Figure 3: Methods used to build archive

1 Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere” Critical Inquiry 23, no. 3 (1997): 660-705.

2 Nabil Beyhum, L’imar Wal’maslaha L’aamma, Fil’ijtimaa Wal’thakafat: Maana L’madina Soukkanuha [Reconstruction and the Public Interest in Meeting and Culture: The Meaning of the City Its Residents]. (Beirut: Dar Aljadid, 1995), 67.

3 Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut”,666.

4 Ibid.

5 Elias Khoury, “The Bulldozers of Memory and the Ruins of the Future.” Al Mulhaq, May 2, 1992. Quoted in Khaled Saghieh, "1990s Beirut: Al-Mulhaq, Memory and the Defeat." e-flux journal, no. #97 (2019).

6 Khaled Saghieh, "1990s Beirut: Al-Mulhaq."

7 Heiko Schmid, “Privatized Urbanity or a Politicized Society? Reconstruction in Beirut after the Civil War.” European Planning Studies 14, no. 3 (2006): 365-81.